Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Introduction

1 The Ugly Duckling

2 The Cipher of Roger Bacon

3 The Magus, the Scryer and the Egyptologist

4 The Cryptological Maze–Part I

5 The Cryptological Maze–Part II

6 A Garden of Unearthly Delights

7 Privileged Consciousness

8 Shams Old and New

9 Letting the Cat out of the Bag

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

A Garden of Unearthly Delights

Gerry Kennedy once again takes up the story of his visit to Yale.

The realisation of a fantasy is proverbially fraught; the long-sought-after has a habit of failing to live up to the dream, and, to make things worse, is subject to the fickle vagaries of a first impression. In July 2001, having travelled up from the Big Apple to Yale University to inspect the fabled Voynich manuscript, I was hoping to gain a clear and calm overview of its delights that up until then had been supplied remotely by a computer screen.

Initially, the sheer privilege of being granted an audience with the volume was excitement enough; I had never before sat reverentially in front of any book, let alone a medieval tome. But somewhere at the back of my mind I possessed images of such rarities, of exotic embellishments to first-line letters or the stylised perspectives of scenes and figures that unfolded as part of a recognisable story. Regardless of one’s acquaintance with ancient volumes, Mary D’Imperio was right to state that the Voynich manuscript stands ‘totally apart’ from other ‘remotely comparable documents’.

Each page (or folio, as I learned to term them, recto facing, verso on the other side) that librarian Ellen Cordes turned, as we progressed through the various sections, revealed fresh wonders for which I had no reference points of any kind. The collection of plants seemed gaspingly surreal, the naked nymphs, whether splashing in ponds or disported on starwheels, sensually whimsical, the medicine jars voluptuously oriental. I struggled to find something of the everyday in it, but felt, like others, that some coherent meaning would emerge if only I looked long and hard enough.

The session lasted about forty-five minutes. This inadequacy was compounded by the aloofness of my bibliographic minder. I attempted to ask a few unprobing questions about how often the volume was shown and to whom, only to be met with complete silence. The ‘look don’t touch’ treatment may have been understandable, but the ‘seen and not heard’ addendum was an unnecessary stricture, turning me from a would-be suitor into a Voynich voyeur. Not only did the book itself seem unreal but the whole context in which I viewed it. Most people, for example, on a visit to savour New York, city of gleaming skyscrapers, would be well advised to take in a bird’s-eye panorama from the top of the Empire State–rather than merely ride its cavernous avenues in a taxi. It was like sightseeing New York on a video played within the taxi.

I exited the revolving doors of the Beinecke Library, carrying a $40 unsatisfactory photocopy of the whole Voynich, feeling as dizzy as if I had spent the last three-quarters of an hour trapped in its portal’s clutches. I wasn’t sure what I had seen except for some document of star-status, clearly so rare and precious that it required the attendant services of a strict bodyguard. Fortunately I had arranged an interview that followed shortly after with another starstruck admirer, whose open enthusiasm reminded me that I was not alone in my infatuation. Phillip Marshall, a postgraduate student in biology at Yale, had seen the manuscript, and as a biologist had naturally concentrated his scientific attention on the large section devoted to plants. We discussed some of the possible identifications he had made. Outside the Beinecke glass box I found it soothing to think that it might be possible to temper a possibly irrational personal attraction with some kind of rational analysis.

Marshall has spent a good deal of time trying to make sense of the illustrations, but like others has met with scant success. If it is extraordinary that the manuscript has resisted decipherment by the most pre-eminent cryptographers of the twentieth century, it is even more so that the copious drawings have not really provided a solid basis to our understanding of it. Codes and ciphers perhaps belong to a specialist realm of study; one would expect concrete images to be more amenable to interpretation. It may turn out that the Voynich script hides a large quantity of written gibberish, but the illustrations do not seem to represent the visual equivalent of mere scrawl or doodling. The strange fact, agreed by many commentators, is that there does appear to be some overall sense of intention behind them, a tentative thematic link.

The illustrations described in chapter 1 divide fairly readily into sections, suggesting a systematic purpose rather than a random rambling. Voynich analysts differ over the precise boundaries of these sections but in general concur that these fall into the herbal, astronomical, astrological or cosmological, balneological (or bathing), and a pharmacopoeia section, including a list of ‘recipes’. We shall view the illustrations utilising these useful headings but perhaps more importantly try to put them in an overarching thematic context.

At a general level the Voynich manuscript’s illustrations evince creative and positive life-generating natural forces, whether relating to the heavens or earth. There are few antagonistic images–no blood, lightning, monsters or mythical beasts that haunted the medieval imagination. There is none of the conflict or destructive tendencies that might be generated pictorially where human interaction and social institutions are concerned. For a medieval document it is surprising that there are almost no references to organised religion or the trappings of secular power, or more mundanely to everyday objects–tools, furniture, means of transport, and so on–that might point historically to a way of life. This creates a sense of otherworldliness and timelessness enhanced by zodiacal drawings of suns, stars, moons and ‘cosmic’ phenomena. Yet this in turn is brought down to earth by the apparent purity, youth and innocence of the naked bathing women undergoing perhaps some esoteric aquatic medical treatment associated with the benefit of the many depicted plants. Are we looking perhaps at some kind of magical herbal treatise that holds contentious secrets for the eyes of only a few?

“If you think all languages have been deciphered, this manuscript offers up a challenge–and provides unique symbols leading to the possibility that it’s a lost alchemical work.”

Diane C. Donovan, California Bookwatch, Dec 2006

• Scholars struggle to decipher 15th-century manuscript.

By John Tiffany —

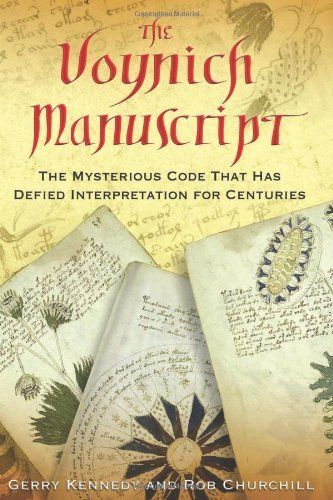

Do you like a good real-life mystery? If so, the story of the Voynich manuscript, documented in the book The Voynich Manuscript: The Mysterious Code That Has Defied Interpretation for Centuries, is a twisting maze.

This mysterious manuscript was discovered in 1912 by a rare book dealer named Wilfrid M. Voynich in a wooden chest at an Italian Jesuit college. To this day, no one knows who the author is, who drew the lavish illustrations or much else about it.

Ever since it was found, the Voynich manuscript has perplexed researchers and scholars. The pages, made of calfskin or vellum, have been carbon dated to the 1400s. Written in an unknown language, the heavily illustrated manuscript was worked on by top code-crackers during World War II. They failed. It’s never been deciphered. At least that is the consensus of opinion. Some Voynichologists believe they have achieved a partial decoding of the document, though.

One section of the book is devoted to botany. Botanist Dr. Arthur Tucker of Delaware State University says he has identified one of the plants as “most certainly” Ipomoea arborescens, a Mexican desert tree that is a relative of the morning glory. Tucker believes the language—Voynichese, if you will—is a form of the Aztec language Nahuatl.

However, some Voynichologists believe Tucker is barking up the wrong tree. A more popular notion is that the Voynich manuscript is connected somehow with Roger Bacon, who flourished in the 13th century, though that is hard to reconcile with the carbon dating of the vellum.

Linguists, who have studied the Voynich manuscript, have determined it is written, like English, from left to right and top to bottom, and that it appears to be a real language, not some random string of nonsense.

Say Gerry Kennedy and Rob Churchill, in their book The Voynich Manuscript: “Many researchers over the years have believed, in all good faith, that they have discovered either a decipherment of the Voynichese language or the real meaning of the strange illustrations. Many more such theories will inevitably be presented in years to come by scholars equally convinced of the correctness of their methodology and conclusions.”

John Tiffany is copy editor for AMERICAN FREE PRESS and assistant editor of THE BARNES REVIEW. He has a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Michigan and has done postgraduate studies in law, biology and computer science. He is devoted to the truth and lets the chips fall where they may.